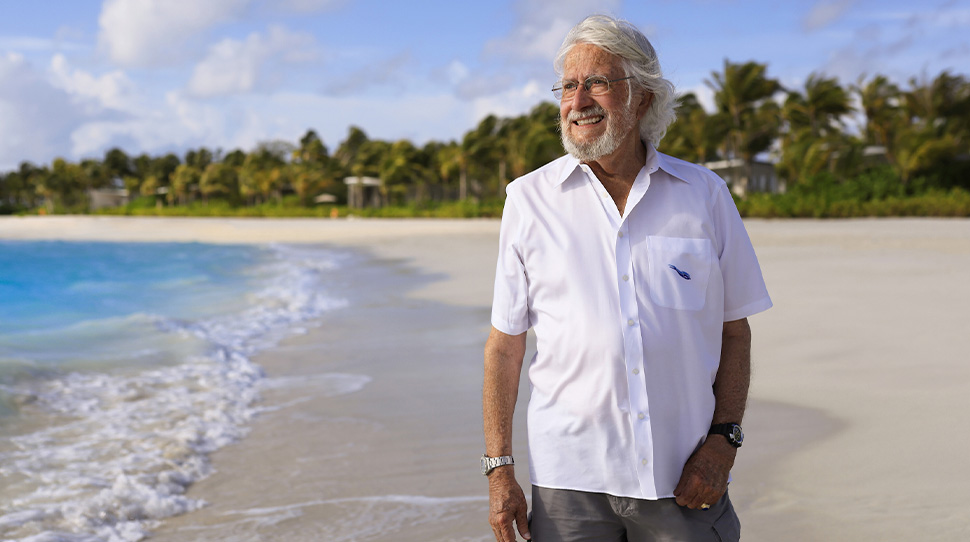

At 84, the celebrated ocean explorer and environmentalist Jean-Michel Cousteau shows few signs of slowing down. The son of the legendary oceanographer Jacques Cousteau, Jean-Michel has dedicated his life to teaching others about the importance of protecting our planet’s oceans and their inhabitants.

That’s the spirit behind his partnership with The Ritz-Carlton on the Ambassadors of the Environment program, which gives guests the chance to explore the breathtaking beauty of local marine life while learning about the importance of preserving these fragile ecosystems for future generations. The program launched at The Ritz-Carlton, Grand Cayman and expanded to other hotels worldwide.

For Earth Day, we sat down with Cousteau at Forbes Travel Guide Five-Star The Ritz-Carlton Maldives, Fari Islands — which debuted the first Ambassadors of the Environment in Asia Pacific — to chat about his commitment to conservation, his underwater adventures since taking up scuba diving at age 7 and a new television series documenting the changes in places across the world that he’s visited.

What are your earliest memories of the ocean?

In the South of France, where I grew up, I was fascinated by all the creatures that I could never see. One that fascinated me was the octopus. They were living right there, and they would change color, change texture, had eight arms and so on.

As a kid, I started catching some of them and selling them so I could buy candy. Today, I would go to jail or be punished. Since then, I’ve learned a lot about the environment and the need to protect it because we’re taking more than nature can produce. We need to protect every species because diversity is synonymous with stability. I think we’re heading in that direction, but time is of the essence.

We also need to have an impact on decision-makers, whether it’s in government or industry. We need to stop pointing fingers at these people because when that happens, they defend themselves. Sit down and try to reach what everyone has, which is a heart. Most of them have families, children and grandchildren, and you want to help them make the bridge between their immediate obligations, decisions or commitments and the future.

I’m more excited than ever because I see progress being made. I was able to reach out to former president George W. Bush, who at the time not only wanted to be re-elected but also promoted the oil and gas industries. I did a film [Jean-Michel Cousteau: Ocean Adventures “Voyage to Kure”] about a region in the ocean 1,200 miles north and a little bit west of Hawaii. I wanted to convince decision-makers that regions like that need to be protected because it symbolizes the ocean, which we are all connected to and depend upon.

We were invited to show the film at the White House. The president invited 50 people to watch it. I was sitting next to his wife, Laura Bush, who asked me a million questions. After the showing, he invited all of us to have lunch, and he asked me to sit next to him. He asked me questions non-stop. At the end of our discussion, he said, “Let’s get it done.” I will never forget that.

Three weeks later, we were invited to the White House, and he signed a document whereby he had created the largest marine protected area on the planet, 1,200 miles long. And then he invited all the people there to watch the film.

Eight or nine years ago, President Obama wanted to see what President Bush had done, and he took an airplane there. After he came back, he said, “I’m going to add another 200 miles.” Republicans and Democrats have agreed to solve this together.

Did your experiences as a child prompt you to create Ambassadors of the Environment?

Absolutely. Because as I got older, I still remembered everything I did when I was a little kid, even if I don’t remember what I was doing last week. When you’re a child, you’re like a sponge, you absorb everything. They also can share what they learn with their parents, friends and neighbors. That’s happening today more and more because we’re living very differently than when I was a kid — I didn’t have a cell phone or computer. But today, everybody has one. So, you have 8.5 billion people who are connected to each other. You can provide information, which they can look up and discuss, and that’s very exciting.

We are the only species that has the privilege to decide not to disappear. But, if we don’t know about what’s happening, we won’t do anything. So, we have a big job there, and I think we’re heading in that direction.

The Maldives has some of the world’s worst microplastic pollution, according to a 2020 report. How has the Indian Ocean changed over the years?

Education is going to make people stop using their neighborhood or their rivers as a destination for trash, thinking, “Oh, it’s gone, I won’t see it again.” Ultimately, with rain, everything makes its way to the ocean. For example, many birds come from other parts of the ocean to one specific location to lay their eggs, and they have to feed those babies before they can fly. So, the parents go and pick up in the ocean whatever they can catch, and a lot of it is plastic — cigarette lighters, toothbrushes and bottle tops — and they regurgitate that into those babies. Millions of them die because they cannot survive.

When I was in Brazil in the middle of the Amazon, there was a lot of pollution such as plastic. We collected it. An industrial company helped us create a book about the Amazon. I have taken journalists to the Amazon, show them the book and I say, “We made this book out of everything that we find here.” Then, I take the book and throw it in the river, and it floats.

Plastic is not the only problem. We must focus on things we never talk about: chemicals and heavy metals. You take a tablet of aspirin because you have a headache. Where’s that chemical going? Right down your system and ultimately into the ocean. Technicians, specialists and so on can help us make a difference. And we are making one.

In your 2012 TED Talk, you said that about 4,000 to 5,000 children under five die every day because they have no water or their water is polluted.

If we really care about our species, we can solve that immediately. If there is no water, there is no life. Polluted water has very much damaged life, and millions of people are dying. We can change that. There’s no excuse today to have any children dying from a lack of water.

What do you want your legacy to be?

I’m not thinking about myself — I don’t care about that. The legacy is for the human species to realize that if we make better decisions and can be much more creative, we have the privilege to decide not to disappear. It’s our choice. If we disappear, nature will keep going on. But I have children and grandchildren, and I’d like them to have the same privilege that I had when I was their age.

What are you working on next?

I’m working on a television series, and I need a lot of help financially to make an investment. I have a not-for-profit company, the Ocean Futures Society, which I created to honor my father when he passed away, and can receive funds to do a series. I want to go to many of the different locations on the planet where I’ve had the privilege of being and show what it used to be like and what it is now. Some have good news, but not all.

This will allow us to better understand the environment we’re connected to and also see the behavior of different species that we didn’t know before. We’re going to focus on whales and dolphins, which are to the ocean what we are to the land. They are warm-blooded, they have families, they are explorers and adventurers, and you find them in 70 percent of the planet. You and I, we’re only on 30 percent. We need to understand that and help protect them.

Where do you like to go on a vacation?

I come to the Maldives. There are many places where I want to go and continue to see how much progress they’re making since I had the pleasure and the privilege of being there before.

Are you still diving?

I am diving every day. And I will dive tomorrow morning at 9 o’clock. I want to go back to where I did a dive to re-see and understand the environment of that location.

What makes the Maldives special to you?

The weather. I think the Maldives is protected from climate change. Why? I don’t know. But it’s been very stable for a long time. This is only our second year here, and I want to come back every year and see our progress.

You seem to never stop learning.

Never. People often ask me, “What was your best dive?” I always tell them, “It’s the next one” because I see either a new species or different behavior and the effect that it has on the environment.

My mission, which should be shared with everybody on the planet as much as we can, is if you protect the ocean, you protect yourself. Wherever you live, you’re connected to the ocean one way or the other. We need to adopt a way of behaving that will help our species.

I’ll be continuing doing what I’m doing until I’m 107 to celebrate 100 years of scuba diving.