French Chef Gilles Epié Makes His Way To Puerto Rico

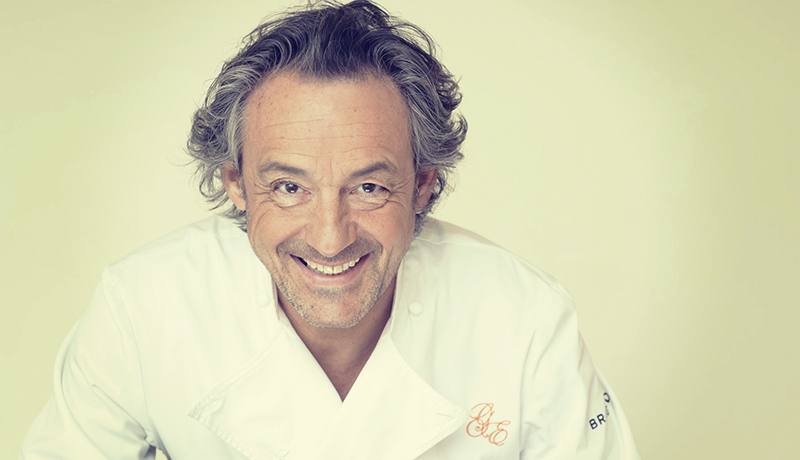

Photo Courtesy of Chateaux Hotels Collection

Occasionally in the food world, the stars align and something magical happens. In this case, the stars are top chefs — Juan Jose Cuevas, the executive chef of 1919 Restaurant at Forbes Travel Guide Four-Star Condado Vanderbilt Hotel, and Gilles Epié, chef-owner of Paris’ Citrus Etoile, who became the youngest Michelin Star winner in history at 22 in 1989 — and the magic is 1919’s Guest Chef Dinner Series, a culinary event that will take place on the beautiful island of Puerto Rico.

For a few short days (November 3 to 5), the chefs will join forces to present a collaborative seven-course menu demonstrating a masterful blend of their combined 40-plus years of experience in kitchens from New York and L.A. to San Sebastian, Spain.

We recently caught up with the chefs to chat about their upcoming event, the changing culinary climate and what keeps them cooking all these years later.

Let’s talk about the Guest Chef Dinner Series and the seven-course menu you’re developing. How closely have you two worked together for the event so far?

CUEVAS: We got in contact two or three months ago. We’ve talked about what kind of ingredients we can get here in Puerto Rico. It’s important for the chef to basically showcase what his food is about, and I will do my best here to get anything he will need for that.

The first thing that we did was exchange menu ideas and [talk about what] we were going to do for the night. Based on that, we said, “Oh, well, maybe this course would be better with this wine” and things like that.

EPIÉ: We’re going share the menu. I’m going to do three dishes and he’s going to do three dishes, so it will be a mix between Puerto Rican and French cuisine. [There’s a] foie gras beignet for an appetizer. I knew that Puerto Ricans would love this beignet, which is a tempura foie gras, caramelized with port wine. And then we’re going do the John Dory [a delicate, white-fleshed fish]. We’re [also] going to do a dessert, a gratin with Champagne sabayon with pineapple and mango. It’s going to be very tasty.

It seems like fresh and local ingredients are definite focal points of your menus. What’s your overall food philosophy?

EPIÉ: My food philosophy is to do something simple. The star of the menu is always the produce. That is why my philosophy is always to have the best produce — the best foie gras, the best fish and the best vegetables — for my menu. Something simple, tasty, full of flavor and, hopefully, everyone’s going to love it.

CUEVAS: For our restaurant, the philosophy is farm-to-table; it’s very similar to what chef Gilles explained. We let the ingredients speak for themselves. Of course, we have a big influence from the Spanish cuisine. The most important thing here is to showcase the ingredients. What you see is what you get, basically.

EPIÉ: When you’re a chef, the most important thing when you cook is the identity of your cuisine. What people love about my cuisine is the fact they can see it’s Epié’s cuisine, not somebody else’s. I create the recipe. That’s why people come to Citrus Etoile — because the identity is mine.

Both of you spent decades abroad before returning home to France and Puerto Rico, respectively. Why’d you decide to go back, and why’d you go back when you did?

EPIÉ: I went back because I’ve always loved a challenge, and I couldn’t find what I was looking for in L.A. When we came back to Paris, we started to plan [Citrus Etoile], and it was difficult to open because you know how much the French — especially the press — don’t like when French chefs come back from the U.S. to Paris.

I brought fusion cuisine back from California, and in the beginning, even my friend Alain [Ducasse] called me and said, “You know, Gilles, you’re using too much Asian cuisine,” and I said, “Okay, but I’m going to keep doing it, whatever. It doesn’t matter.”

So I brought something interesting to Paris, and we built up, my wife and myself, a business right on the Champs Élysées. We worked really hard for it, and now we’re full all the time, even after the attacks and [with the state of] the economy. It is a really, really bad time for the restaurant business and hotels in Paris right now. One day we’re going to go back to the States because we don’t have to prove anything to anyone else any more.

CUEVAS: Well, for me, I basically lived half of my life in Puerto Rico and then the second half in the States and Spain mostly. After traveling and working many places, I can now say I am in the best place. It is very good to be back home, very good to see how much Puerto Rico has changed since I left home 20 years ago. Before, it was a very continental cuisine, very hotel-oriented. Nowadays, produce-wise, it is so much better; there is direct correlation between farming and what chefs are doing on the island. [The island] is definitely more open to different kinds of cuisine and techniques — definitely more modern, less classical also.

Have you discovered any differences in cooking for diners in the States versus diners in Puerto Rico or France? Are the expectations different?

EPIÉ: French people, of course, are really complicated. They know about cooking; they know about food. French people, they go for dinner; they don’t go just to eat. And in America, mostly they eat and go. In Paris, sometimes they stay for two or three hours at the table; they live for food and they live to drink wine. That’s why Paris is still Paris.

What I love most in Paris is the competition. Where we are located is home to some of the biggest competition in the world, some of the biggest Michelin-starred chefs on earth. That’s why we have to work hard.

CUEVAS: For me, all three places have been completely different markets. The expectation from the guests is always that they want to have a great time. Back in New York, it’s a little more intense. California is a little more laid back but, of course, the food is lighter and less European. In Puerto Rico, there is more freedom; it’s more laid back and relaxed. They love to stay and talk and chit chat for a very long time.

When I moved here four years ago, one of the first things I said to myself was that I had to take New York out of my head. Every time you go to a new market, the guests are going to be different. The only thing that can never change is the quality of what you serve and what your food is.

Being a chef and working in kitchens is hard and sometimes thankless work, so what made you keep going? What made you succeed when so many others did not?

EPIÉ: On my side, you know, I started working in kitchens when I was 14 years old. I grew up in the kitchen all my life, so that’s the only thing I know how to do. What keeps me going is the fact that I love what I do. I love people, which is the most important thing. To be a good chef, you have to love people. If you don’t like people, you’re not going to be able to sell great food. I love the fact that I can create something from scratch and bring people in every day. The biggest pleasure I get from that is when you see people leaving and they say, “Make me a reservation for next week” or tomorrow or the next day, you know. That’s the biggest thing, especially when there was a bad economy in France. I don’t know what we did, but we’re doing something right.

CUEVAS: I say this has to be one of the top three professions where you really have to love it. There’s a passion [for] it that drives you every day. There’s a passion for meeting people, taking new food and inventing something new. . .If I were to die and begin my life again, I would 100 percent do the same thing. It’s definitely hard, you know, long hours, and it’s really rough sometimes, but there’s something about it that brings you back every day.

EPIE: It’s never hard to work so much if you love what you do. It doesn’t matter. I never count the hours of my day; I just do it because I love it.